A remarkable discovery of previously unseen doodles by the English poet and painter William Blake has been made using advanced technology, revealing etchings that date back around 250 years. These faint engravings, found on copper plates, provide new insights into Blake’s early years as an apprentice, long before he became one of the most celebrated poets and artists of his time.

Blake, best known for his poems such as “Jerusalem” and “The Tyger,” trained under James Basire, an engraver who produced pictorial prints, a popular method for illustrating books in the 18th century. Blake’s apprenticeship involved detailed and repetitive engraving tasks, but it appears that during his downtime, the young artist filled the backs of Basire’s copper plates with his own small doodles.

The engravings, which are almost invisible to the naked eye, were discovered using cutting-edge, high-resolution scanning technology at Oxford’s Bodleian Libraries. The copper plates had been part of the library’s collection since 1809, but it wasn’t until researchers applied modern imaging tools that the delicate engravings were revealed.

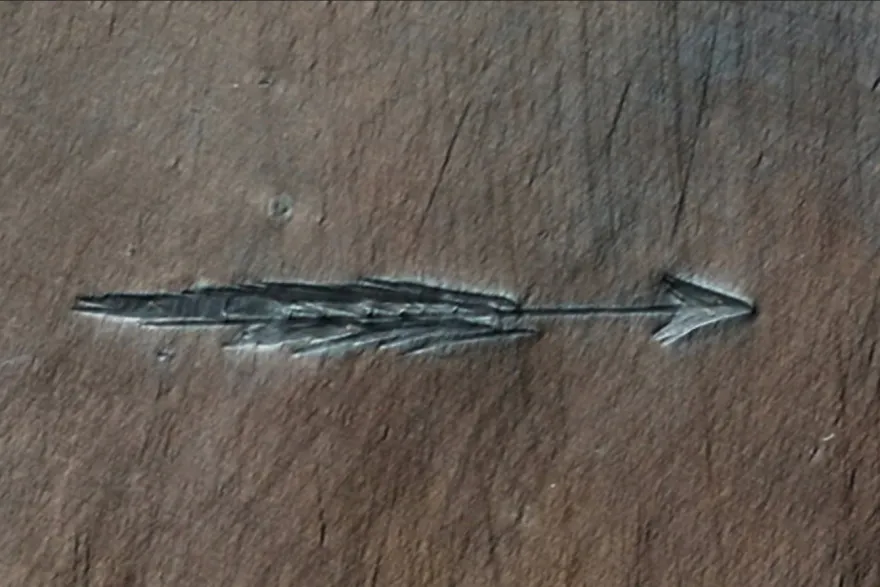

One of the doodles features an arrow, a motif that would recur throughout Blake’s later work, while another shows a tiny face. Mark Crosby, a Blake expert and associate professor at Kansas State University, led the discovery and was astonished when he first laid eyes on the hidden drawings. “It was a staggering moment,” Crosby said. “Looking back at something that had been created over 250 years ago but had remained unseen felt surreal.”

The location of the engravings on the reverse side of Basire’s plates, coupled with the themes and style, strongly indicates that Blake was the artist behind them, even though the plates do not bear his signature. Crosby suggested that the young Blake likely made these doodles while practicing and experimenting with his engraving techniques during his apprenticeship. The drawings offer a glimpse into the mind of a teenage Blake, who may have been seeking relief from the monotony of repetitive tasks by expressing his creativity in these small, private sketches.

Crosby’s research, which will be published in two peer-reviewed journals, highlights the importance of technological advances in art history. The discovery not only provides a new understanding of Blake’s early artistic development but also sheds light on the daily life of apprentices in 18th-century engraving studios. These doodles, though simple, offer a rare glimpse into the formative years of one of England’s greatest artistic figures.

READ MORE: